The world is ready to reclaim cooking

and Parsnip is just in time to make it happen!

One of the very nicest things about life is the way we must regularly stop whatever it is we are doing and devote our attention to eating.

— Luciano Pavarotti

Parsnip’s mission is to make home-cooked food easy and convenient for anyone in the world, and the app we’re about to launch is a huge step forward. But this post isn’t just about Parsnip—it’s a story of how ancient and modern history have converged into colossal tailwinds at our back.

Humankind’s First Technology

Cooking feels so quaint, doesn’t it? Making our own food is so old school—who even has time for that anymore? Life moves way faster than it did for our grandparents, or even our parents, and eating is far more convenient today.

But, let’s rewind to the dawn of humankind. Cooking is up to a million years old, one of the first things we learned after discovering fire, and our earliest technology for processing food.

Fundamentally, cooking provides sustenance, and it was probably critical to the evolution of homo erectus. Cooked food made it easier to absorb nutrients, providing energy to fuel our larger brains, and eventually led to agriculture, settlements, and humans spending less time gathering food and more doing other “useful” things.

Over time, food became much more than just fuel for our bodies. It appeared in the earliest prehistoric art and grew to be central to the cultures of entire countries. Eating around a table is sacred around the world. Fellowship around food is the great connector, the place where relationships—and ultimately communities—are formed.

“Eating is so intimate. It's very sensual. When you invite someone to sit at your table and you want to cook for them, you're inviting a person into your life.”

— Maya Angelou

Yet even more, cooking allows us to experience the joy of a creative and rewarding endeavor on a daily basis, making something and enjoying the fruits of our labor, and then delighting in serving that to others.

“A good cook is like a sorceress who dispenses happiness.”

— Elsa Schiaparelli

So, cooking fulfills a basic need we have at least 3 times a day—to eat. But it also fosters relationships, culture, and creativity. In a previous post about our mission, we discussed the Lindy effect: the durability of an idea or technology is proportional to how long it’s been around. We may have forgotten why, but cooking is here for good reason, and it’s going to be around for a long time.

Technology + Food = the Future?

Technological advancement often makes our lives more fluid and convenient. When it comes to food, cooking can be slow—and we want to eat now! Why not apply economies of scale to food creation, outsourcing food processing in the name of efficiency and convenience? After all, food is our fuel and the faster it gets in our belly, the better.

As with many technologies, it was war that precipitated advances in industrial food processing, starting as early as World War II. Probably half the food we eat today was influenced by food science derived from military applications1. “An army marches on its stomach” is a universal truth throughout history, as we are reminded once again.

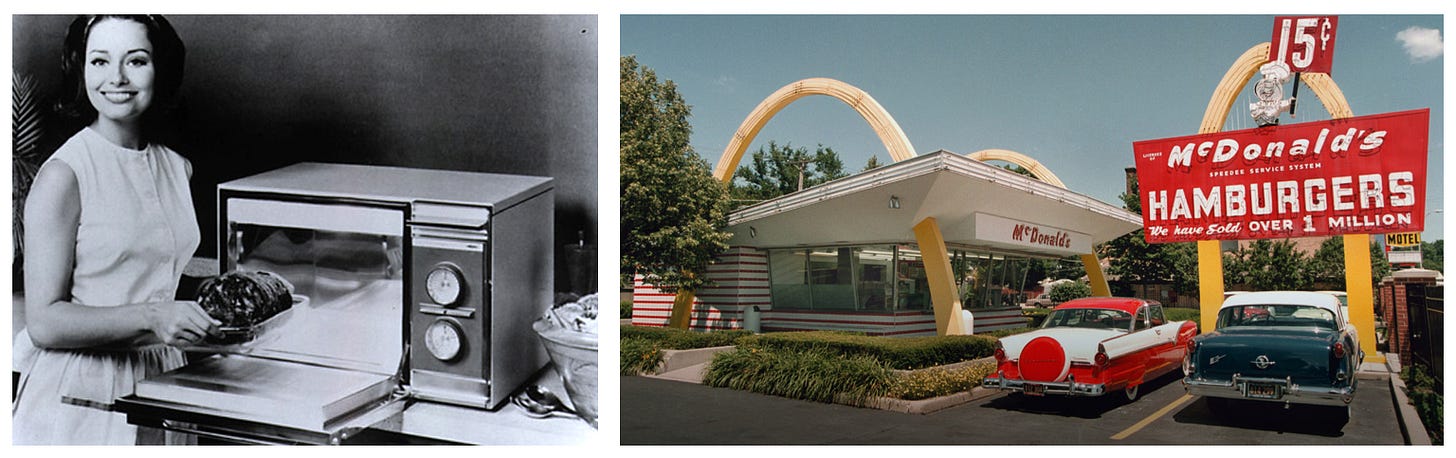

In the post-war boom of the 1960s, food preservation technologies filtered from the military into our homes. Microwaves were a huge boon to those preparing food at home. The magic of reheating pre-processed foods saved so much effort over cooking from scratch. Meanwhile fast-food restaurants, with McDonald’s leading the charge, were just beginning their march to world domination.

Skip ahead a few years, and we process more and more food outside the home. Why bake from cake mix when you can get a pre-packaged cake that lasts weeks2?

People began to demand the full bounty of eating any produce at any time of the year, seasons be damned. The modern food supply chain is a miracle that can ship blueberries from the Peruvian summer to the American winter, ripe and sweet enough to eat. By scaling up meat production to industrial levels, chicken became a rare meat that was enjoyed only on Sundays, to a $1/pound mass-produced product that Popeyes sells by the bucket. This is how we feed the world, right?

Now, it’s 2022—and do we even need the kitchen at all? Food can be ordered on an app and delivered to your door in 30 minutes3. But then, why have restaurants at all? That whole customer-facing front-of-house part is a huge cost center, so let’s just cut it out and go with ghost kitchens. And soon, if we’re lucky, we can probably replace those pesky humans delivering, and cooking, food—with robots!

Maybe this isn’t the world we want to live in

History shows us again and again that more technology doesn’t magically improve the world, and food tech is no exception. In our digital age, we have prioritized convenience over culture, efficiency over craft, and quick dining over generational recipes. In today’s world, we seem to have forgotten what makes food… well, good.

Some think of food as fuel, at meals as something to outsource. Despite the profusion of information on the Internet, learning to cook is harder than ever. We used to watch our parents in the kitchen or learn home economics in our schools, but those avenues have faded. YouTube and TikTok are the closest replacements, but their main goal is to monetize eyeballs with ads, not teach. When we can’t cook, we also can't eat together.

Ironically, the food tech land grab isn’t even producing great businesses. Consider food delivery companies like GrubHub and DoorDash. Local restaurants pay up to 30% of revenue just to participate in the delivery ecosystem, ostensibly to market their brand. But as delivery becomes the norm, they’re locked into a money-losing doom loop with no way out. Often, food delivery accelerates the demise of restaurants while simultaneously exploiting delivery workers—a perfect storm of destruction.

How about 15-minute grocery delivery, for which over a dozen companies raised enormous venture funding since the pandemic began? A year later, they’re already flagging, with two shutting down in the same week. Unfortunately, the irrational exuberance of free money is no match for the stark reality of unit economics—there’s just no juice to squeeze in the super low margins of grocery.

There are only two ways to improve margins in meal & grocery delivery: raise prices or cut costs. You can’t raise prices for an undifferentiated product, so cutting costs means paying delivery workers less, forgoing the restaurant for a ghost kitchen, or just removing humans from the picture altogether. Any way we slice it, we’re hurtling into a world of outsourced food production, done as cheaply as possible.

At the same time, we’ve also scaled up agriculture to gigantic proportions, and many of our farms look like factories. The worst offenders require tons of fuel, feed, and fertilizer as inputs, and spew agricultural runoff and greenhouse gases. Animals are often treated poorly, and we’re not even producing good quality products, with antibiotic-laden meat and Roundup Ready crops doused with pesticides4.

So, having taken our culture of convenience to the extreme, we now suffer the consequences:

We don’t eat together, avoiding other people while we can’t feed ourselves. Instead, we ogle influencers on social media, turning sustenance into entertainment while waiting for food that arrives in a bag.

We’re outsourcing cooking to businesses that exploit workers and destroy communities—and they aren’t even good businesses!

The way we’re producing food is poisoning people and the planet.

Alas, cooking has slowly transitioned from an absolute necessity for everyday life to a luxury afforded only to those with the time, the resources and the know how. How did such a fundamental necessity of life become tied to class and status?

Learning to reclaim what’s lost

As we slowly realize that we’re eating junk while damaging the planet along the way, a slow but spreading desire for change is emerging worldwide—to make our own food again, and care about where it comes from.

People all over the world are rediscovering food culture on the verge of being lost, such as homemade kimchi in South Korea and sourdough baking during lockdown. We’re starting to learn about the negative externalities of industrial food production, and possibility of farming in a way that is self-sufficient and doesn’t depend on huge inputs of fuel or fertilizer5. There’s rising awareness of how highly processed food harms us, and greater care for the quality of food that we eat: the idea of “food as medicine”.

And finally, we’re cooking more—honing that essential, daily skill that brings us closer to our food. But learning what we’ve lost from scratch is hard! Cooking is an apprenticeship skill, and we’ve lost many of our masters—parents, grandparents, schools. In a cruel twist of fate, knowledge is more available than ever, but it’s also harder than ever to find.

A silver lining of the pandemic is that it was an incredible accelerator for home cooking. Millions became intimately familiar with their kitchen, even against their will. Sourdough baking became a cliche. Viral TikToks caused entire regions of the world to run out of feta cheese and Kewpie mayo. It turns out people don’t want food entertainment—they just want simple, easy food that they can make, and eat, at home. As we enter a world of permanent remote work, the demand for home cooking has increased permanently & indefinitely.

Here we are, then, with the stars aligned for a resurgence in home cooking:

Social forces have inverted over the last 60 years, with more people wanting to cook yet it being harder to learn than ever.

COVID forced many people to get comfortable with their kitchen, and remote work has permanently reshaped the landscape for home cooking.

We’re probably on the precipice of a recession, which greatly increases demand for affordable food.

Parsnip: technology that reboots tradition

The burgeoning, pent-up pressure to get our hands dirty and make our own food is universal, and people are looking for a release valve. Here’s the simplest way to see that the market is ripe for Parsnip:

So, what if we could we make cooking… the most convenient way to eat?

We believe that food tech doesn’t just have to be delivery apps, the gig economy, meal kits, or cooking robots. Instead, Parsnip is a new kind of food tech that empowers people by supercharging how they get knowledge into their brain. As we expand to advanced capabilities powered by data and machine learning, we’ll also help everyone make better decisions about how to feed themselves every day.

Parsnip is taking one of the oldest technologies ever and reimagining it with the best parts of edtech, consumer tech, and computer science. If we succeed, we make cooking 10x easier and empower anyone, anywhere in the world, to enjoy how food ought to be, in their homes, with their friends and family, and with benefits that overflow to both people and the planet.

Please try out our beta and stay tuned for our upcoming release in the App Store!

In a future memo, we’ll explore how Parsnip will also make cooking convenient beyond simply helping people to learn.

Combat-Ready Kitchen is a great book on military influence in the history of food.

The original Twinkie sold in the 1930s had a shelf life of 2 days. A new formula for Twinkies nearly doubled their “fresh” shelf life from 26 to 45 days. But in a pinch, you might still be able to eat them 8 years later!

Unless GrubHub is running a free lunch promotion. Then you might be among the thousands of irate people that didn’t get fed.

The agriculture lobby is the most powerful in America, enjoying bipartisan support, so this is unlikely to change without a bottoms-up way to somehow influence the eating behavior of millions of consumers. What could possibly do that? 😉

Farms are ideally self sufficient, without the need for large quantities of fuel or industrially produced fertilizer. Instead, animals can help to aerate the soil and also fertilize crops. Two examples are Bec Hellouin (described in Miraculous Abundance) and Polyface Farm.